Over time, wood undergoes a series of natural and environmental transformations that alter its structure, appearance, and functionality. Exposure to elements like moisture, sunlight, and temperature fluctuations can lead to weathering, causing the wood to crack, warp, or fade. Biological factors, such as fungi, insects, and bacteria, contribute to decay, breaking down the cellulose and lignin that compose the wood. Additionally, in the absence of oxygen, wood buried in anaerobic conditions, like wetlands, can fossilize into materials like coal over millions of years. Human intervention, such as preservation techniques like drying, treating, or storing in controlled environments, can slow these processes, but ultimately, wood’s longevity depends on its environment and the forces acting upon it.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Color Change | Wood darkens or lightens over time due to exposure to UV light, oxygen, and moisture. |

| Strength Loss | Wood loses strength and becomes more brittle due to degradation of cellulose and lignin. |

| Warping & Cracking | Wood warps, cracks, or splits due to changes in moisture content and temperature fluctuations. |

| Rot & Decay | Wood is susceptible to fungal decay and insect damage, especially in damp conditions. |

| Surface Checking | Fine cracks appear on the surface due to drying and shrinkage. |

| Texture Changes | Wood may become rougher or smoother depending on exposure and wear. |

| Density Reduction | Wood density decreases as fibers break down and voids form. |

| Chemical Degradation | Lignin and cellulose degrade due to oxidation, hydrolysis, and biological activity. |

| Fossilization | In rare cases, wood can fossilize over millions of years, turning into materials like coal or petrified wood. |

| Loss of Resins & Oils | Natural resins and oils in wood may evaporate or degrade over time. |

| Microbial Activity | Fungi, bacteria, and insects accelerate wood degradation in humid environments. |

| Preservation Effects | Treated wood (e.g., pressure-treated or painted) may resist decay longer than untreated wood. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Natural Decay Processes: Fungi, bacteria, and insects break down wood fibers over time

- Weathering Effects: Sun, rain, and wind erode wood surfaces, causing cracks and discoloration

- Fossilization: Wood buried in sediment can turn into fossils like coal or petrified wood

- Human Preservation: Treatment with chemicals or controlled environments slows wood deterioration

- Archaeological Significance: Aged wood provides insights into history, climate, and ancient civilizations

Natural Decay Processes: Fungi, bacteria, and insects break down wood fibers over time

Wood, once a living, growing material, is not immune to the relentless forces of nature. Left untreated and exposed to the elements, it becomes a feast for fungi, bacteria, and insects, all of which play a crucial role in the natural decay process. This breakdown is not merely a destructive force but a vital part of the ecosystem, returning nutrients to the soil and completing the life cycle of the tree.

Consider the role of fungi, the primary decomposers of wood. These microscopic organisms secrete enzymes that break down complex wood fibers, such as cellulose and lignin, into simpler compounds. For instance, white rot fungi excel at degrading lignin, while brown rot fungi target cellulose. This process, known as biodegradation, can reduce the strength of wood by up to 50% within a decade in humid environments. To slow this decay, wood should be kept dry and treated with fungicides, as moisture levels above 20% accelerate fungal growth.

Bacteria, though less prominent than fungi, also contribute to wood decay, particularly in aquatic or waterlogged environments. These microorganisms thrive in anaerobic conditions, breaking down wood through fermentation processes. For example, in wetlands, bacteria can degrade wood at a rate of 1-2% per year, depending on temperature and oxygen availability. Preventive measures include using water-resistant wood species like cedar or applying preservatives such as creosote, which inhibit bacterial activity.

Insects, while not decomposers themselves, weaken wood structures by creating entry points for fungi and bacteria. Termites, carpenter ants, and wood-boring beetles are among the most destructive. Termites alone cause billions of dollars in damage annually, consuming wood at rates of up to 15 grams per termite per day. To protect against insect damage, use pressure-treated wood or apply insecticides like permethrin. Regular inspections and prompt removal of infested wood are also essential.

Understanding these decay processes allows for better wood preservation strategies. For outdoor structures, combine multiple methods: treat wood with preservatives, ensure proper ventilation to reduce moisture, and periodically inspect for insect activity. By mimicking nature’s balance, we can extend the lifespan of wood while minimizing environmental impact. After all, the goal is not to halt decay entirely but to manage it sustainably, honoring the material’s role in both human use and ecological cycles.

Understanding Wood EMC: Timeframe for Equilibrium Moisture Content

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Weathering Effects: Sun, rain, and wind erode wood surfaces, causing cracks and discoloration

Wood, when exposed to the elements, undergoes a relentless transformation, a process both beautiful and destructive. The sun, rain, and wind act as nature's artists, carving and painting the wood's surface over time. This weathering effect is a testament to the power of the environment, leaving behind a unique, aged appearance that tells a story of endurance.

The Sun's Role: A Double-Edged Sword

Imagine a wooden fence, once vibrant and smooth, now bearing the marks of time. Prolonged exposure to sunlight is a primary culprit in wood's deterioration. Ultraviolet (UV) rays penetrate the wood's surface, breaking down its cellular structure. This process, known as photodegradation, causes the wood to become brittle and weak. Over time, the sun's rays can lead to the formation of cracks, especially in areas with high UV exposure, such as south-facing surfaces. Interestingly, the sun's impact is not uniform; it can create a unique, weathered look with varying shades of gray and brown, often sought after in rustic design.

Rain's Persistent Attack

Rainwater, a seemingly gentle force, contributes significantly to wood's erosion. When rain falls on wood, it seeps into the material, causing it to expand. As the wood dries, it contracts. This constant cycle of wetting and drying leads to the development of cracks and checks, especially in areas with high rainfall. For instance, wooden outdoor furniture may exhibit deep cracks along the grain after several seasons, requiring regular maintenance to prevent further damage. The key to mitigating rain's impact lies in proper sealing and regular reapplication of protective coatings.

Wind's Abrasive Nature

Wind, often overlooked, plays a crucial role in wood's weathering. It carries abrasive particles like dust and sand, which act like natural sandpaper on wood surfaces. Over time, this abrasion can lead to a smooth, weathered appearance, particularly on windward sides. In coastal areas, where wind speeds are higher, this effect is more pronounced. For example, beachfront wooden structures may exhibit a unique, polished look on the side facing the ocean due to the constant wind and salt spray.

Practical Tips for Wood Preservation

To combat these weathering effects, consider the following:

- Sealing and Staining: Apply a high-quality wood sealant or stain to create a protective barrier against moisture and UV rays. Reapply annually or as needed, especially in harsh climates.

- Regular Cleaning: Remove dirt and debris to prevent abrasion. Use a mild detergent and a soft brush to clean wood surfaces regularly.

- Strategic Placement: When possible, position wooden structures to minimize direct sun exposure and prevailing winds.

- Repair and Maintenance: Inspect wood regularly for cracks and damage. Fill cracks with appropriate wood fillers and consider professional restoration for valuable wooden items.

In the battle against nature's elements, understanding these weathering effects is crucial for anyone working with wood. By recognizing the unique impact of sun, rain, and wind, one can take proactive measures to preserve wood's beauty and integrity, ensuring it stands the test of time. This knowledge is particularly valuable for outdoor wood applications, where the environment's artistry can be both a blessing and a challenge.

Exploring Muir Woods: Average Walking Time and Trail Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fossilization: Wood buried in sediment can turn into fossils like coal or petrified wood

Wood buried deep within sediment undergoes a remarkable transformation over millennia, a process known as fossilization. This natural phenomenon turns organic material into enduring relics of Earth’s history, preserving wood in forms like coal or petrified wood. The journey begins when wood is rapidly buried, shielding it from oxygen and decay-causing organisms. Over time, minerals seep into the wood’s cellular structure, replacing organic matter with silica, calcite, or pyrite, creating petrified wood—a stone-like replica of the original tree. This process, called permineralization, requires specific conditions: anaerobic environments, mineral-rich groundwater, and immense pressure. The result is a fossil that retains the wood’s original texture and structure, offering a window into ancient ecosystems.

Coal, another product of wood fossilization, forms through a different mechanism. Unlike petrified wood, coal originates from compressed plant material, often in swampy environments. Over millions of years, layers of sediment bury the wood, subjecting it to intense heat and pressure. This drives off volatile compounds, leaving behind carbon-rich material. The type of coal—peat, lignite, bituminous, or anthracite—depends on the duration and intensity of this process. For instance, anthracite, the hardest coal, forms under the highest pressure and heat, retaining up to 95% carbon. This transformation highlights how fossilization not only preserves wood but also converts it into a valuable energy resource.

To understand fossilization, consider the steps required for wood to become petrified. First, the wood must be buried quickly, often by volcanic ash, mudslides, or river sediment. This prevents decay and creates an oxygen-free environment. Next, groundwater rich in dissolved minerals like silica or calcite must permeate the wood. Over centuries, these minerals crystallize within the wood’s cells, gradually replacing organic material. Finally, the surrounding sediment hardens into rock, entombing the petrified wood. Practical tip: collectors seeking petrified wood often look in areas with volcanic history, such as Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, where silica-rich ash preserved ancient trees in stunning detail.

Comparing petrified wood and coal reveals distinct outcomes of fossilization. Petrified wood retains the original structure of the tree, allowing scientists to study ancient plant species and environments. Coal, however, loses all cellular detail, becoming a homogeneous mass of carbon. This difference underscores the importance of fossilization conditions: petrification requires mineral infiltration, while coal formation relies on compression and heat. Both processes, however, serve as time capsules, preserving evidence of Earth’s past climates and ecosystems. For educators, using petrified wood and coal in lessons can illustrate the diversity of fossilization and its role in understanding geological history.

Fossilization is not merely a scientific curiosity but a process with practical implications. Petrified wood, for instance, is prized in lapidary arts for its vibrant colors and patterns, though collectors must adhere to regulations protecting natural specimens. Coal, despite its environmental drawbacks, remains a critical energy source, powering industries worldwide. Understanding fossilization also aids in predicting where fossil fuels or ancient plant fossils might be found, guiding geological surveys. By studying these processes, we gain insights into Earth’s history and resources, bridging the gap between past and present. Whether for scientific research, education, or resource management, fossilization remains a fascinating and essential natural process.

Glulam vs. Wood: Which Material Offers Superior Longevity?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Human Preservation: Treatment with chemicals or controlled environments slows wood deterioration

Wood, left untreated, succumbs to the relentless forces of nature: moisture, insects, fungi, and sunlight. These agents break down its cellular structure, leading to decay, warping, and eventual disintegration. Yet, human ingenuity has devised methods to defy this natural process, preserving wood for centuries. Chemical treatments and controlled environments stand as testaments to our ability to slow the march of time, ensuring that wooden artifacts, structures, and treasures endure.

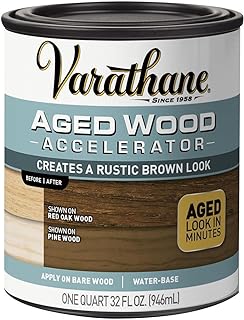

Chemical treatments act as a shield, penetrating the wood’s fibers to repel invaders and stabilize its composition. Common preservatives include creosote, copper azole, and borates, each tailored to specific threats. For instance, borates are highly effective against fungi and insects, making them ideal for indoor applications. Treatment involves immersing the wood in a preservative solution or applying it under pressure to ensure deep penetration. Dosage varies by wood type and intended use; for example, outdoor furniture might require a 0.1% borate solution, while structural timber could need higher concentrations. Always follow manufacturer guidelines and wear protective gear, as these chemicals can be hazardous.

Controlled environments offer another avenue for preservation, manipulating factors like humidity, temperature, and light to inhibit decay. Museums and archives often store wooden artifacts in climate-controlled rooms with humidity levels below 50% to prevent mold growth. For smaller items, desiccant-filled containers or vacuum-sealed bags can create micro-environments that stave off deterioration. Light exposure should be minimized, as ultraviolet rays accelerate wood degradation. Practical tips include using UV-filtering glass for display cases and rotating exhibits to limit exposure.

Comparing these methods reveals their complementary strengths. Chemicals provide active protection against biological threats, while controlled environments address environmental stressors. Combining both approaches yields the best results, particularly for high-value or historically significant wood. For example, a medieval wooden sculpture might be treated with borates to prevent insect damage and then stored in a climate-controlled vault to safeguard against humidity and temperature fluctuations.

The takeaway is clear: human preservation techniques can dramatically extend wood’s lifespan, but success hinges on precision and care. Whether treating a backyard deck or a priceless artifact, understanding the wood’s vulnerabilities and selecting the appropriate method is crucial. By harnessing chemistry and environmental control, we not only preserve wood but also the stories and craftsmanship it embodies, ensuring they endure for generations to come.

Maximizing Your Wood Deck's Lifespan: Factors and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Archaeological Significance: Aged wood provides insights into history, climate, and ancient civilizations

Wood, when preserved over centuries or millennia, becomes a silent archivist of the past. Its cellular structure, chemical composition, and physical state encode data about the environments it endured and the civilizations that shaped it. Archaeologists treat aged wood not merely as a relic but as a multidimensional record, decipherable through techniques like dendrochronology, radiocarbon dating, and stable isotope analysis. Each method unlocks a layer of information—tree-ring patterns reveal annual climate fluctuations, while carbon isotopes trace ancient diets or environmental conditions. This material, often unearthed from waterlogged sites, shipwrecks, or arid deserts, offers a temporal precision unmatched by other organic remains.

Consider the practical steps in extracting historical insights from aged wood. First, dendrochronology—the study of tree rings—provides chronological anchors. By cross-referencing ring patterns with known chronologies, researchers can date artifacts to within a single year. For instance, oak beams from a medieval church in England were dated to 1234 AD, aligning with historical records of its construction. Second, radiocarbon dating measures residual carbon-14 to estimate age, though with a margin of error (typically ±40 years for samples over 2,000 years old). Combining these methods ensures accuracy, as demonstrated in the analysis of Viking Age ship timbers from Norway, where dendrochronology refined radiocarbon estimates to specific decades.

The persuasive case for aged wood’s value lies in its ability to bridge gaps in historical and environmental records. For example, wooden tools from a 9,000-year-old settlement in Jordan revealed early agricultural practices, while pollen trapped in the wood identified contemporaneous crops. Similarly, stable isotope analysis of cellulose in ancient wood can reconstruct past precipitation levels, as seen in studies of Roman-era timber from the Alps, which correlated periods of heavy rainfall with historical accounts of crop surpluses. This interdisciplinary approach transforms wood from a passive artifact into an active storyteller, challenging or confirming existing narratives.

Comparatively, aged wood’s archaeological significance surpasses that of stone or metal artifacts in certain contexts. While stone tools endure, they rarely preserve organic residues or environmental data. Metal corrodes, losing contextual clues over time. Wood, however, retains traces of its origin and use—a 3,000-year-old Egyptian coffin’s cedar planks, for instance, bore resin pockets that identified their Lebanese source, confirming trade routes described in ancient texts. This material specificity makes wood indispensable for reconstructing cultural exchanges, technological advancements, and ecological shifts.

To maximize the utility of aged wood in research, preservation is paramount. Waterlogged wood, such as that from Bronze Age pile dwellings in Switzerland, must be treated with polyethylene glycol to prevent shrinkage upon drying. For arid-preserved specimens, like those from Egyptian tombs, controlled humidity storage prevents cracking. Researchers should also prioritize non-destructive sampling—extracting micro-samples for analysis rather than compromising the artifact’s integrity. By adhering to these practices, archaeologists ensure that aged wood continues to yield discoveries, from the daily lives of ancient peoples to the climatic upheavals that shaped their worlds.

Standard Full-Size Wooden Bed Slats Length Explained: A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wood exposed to the elements over a long period will degrade due to weathering, moisture, UV radiation, and insect damage. It may crack, warp, rot, or become discolored as its natural fibers break down.

In a controlled environment with stable temperature and humidity, wood can remain stable for centuries. It may dry out and shrink slightly, but it is less likely to rot or warp, preserving its structural integrity.

Wood buried underground can either decompose completely due to moisture and microbial activity or become fossilized under specific conditions, turning into materials like coal over millions of years. Preservation depends on oxygen levels and soil composition.

![Furniture Glaze - Antique Patina Special Effects Glaze for Chalk Style Furniture Paint, Eco-Friendly Wood Stain, 6 Color Choices - Slate [Grey] - Pint (16 oz)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51GAvNLyf1L._AC_UL320_.jpg)