Agate petrified wood, a mesmerizing fusion of mineral and fossil, forms through a slow and intricate process that spans millions of years. Beginning with the burial of ancient trees, typically in sediment-rich environments like riverbeds or volcanic ash, the organic material is gradually replaced by minerals such as silica, often carried by groundwater. Over time, the wood’s cellular structure is meticulously replicated by these minerals, transforming it into a stone-like substance while retaining its original texture and patterns. The formation of agate, characterized by its banded or layered appearance, adds an additional layer of complexity, requiring specific conditions of pressure, temperature, and mineral availability. This entire process, from the initial burial to the final crystallization, can take anywhere from 5 to 20 million years, making agate petrified wood a testament to the Earth’s patience and geological artistry.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Formation Time | Millions of years (typically 10-100 million years) |

| Process | Fossilization through permineralization |

| Key Minerals Involved | Quartz (silica), chalcedony, agate |

| Parent Material | Wood from ancient trees (e.g., conifers, ferns) |

| Environmental Conditions | Sedimentary environments (e.g., volcanic ash, mud, or waterlogged areas) |

| Water Role | Essential for transporting silica-rich minerals |

| Pressure and Temperature | Low to moderate pressure and temperature |

| Preservation of Structure | Cellular structure of wood is often preserved |

| Coloration | Varies based on impurities (e.g., iron, manganese, carbon) |

| Hardness (Mohs Scale) | 7 (due to quartz content) |

| Examples of Locations | Petrified Forest National Park (USA), Argentina, Indonesia |

| Significance | Provides insights into ancient ecosystems and geological history |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Agate Formation Process Overview

Agate formation is a geological process that transforms organic materials, such as wood, into stunning mineralized structures through a combination of silica deposition and environmental conditions. This transformation, often referred to as petrification, begins when a tree dies and its organic matter is buried under sediment, shielding it from decay. Over time, silica-rich groundwater seeps into the wood, replacing the original cellular structure with microscopic quartz crystals. This process, known as permineralization, is the cornerstone of agate petrified wood formation. The key to understanding its timeline lies in the interplay of silica availability, temperature, and pressure, which collectively dictate the pace of mineralization.

The duration of agate formation varies widely, typically spanning thousands to millions of years, depending on environmental factors. In regions with abundant silica, such as volcanic areas or silica-rich sedimentary basins, the process can accelerate. For instance, the renowned petrified forests in Arizona formed over 225 million years, benefiting from silica-laden waters derived from volcanic ash. Conversely, in less silica-rich environments, the process may take significantly longer. Temperature plays a critical role as well; warmer conditions expedite silica precipitation, while cooler settings slow it down. Pressure, often from overlying sediment, aids in compacting the wood and facilitating mineral infiltration. These variables make each agate specimen a unique product of its geological history.

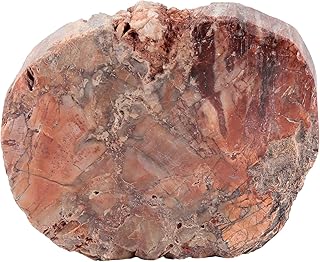

To illustrate the process, consider the steps involved in agate petrified wood formation. First, the wood must be buried rapidly to prevent decay, often by sediment accumulation in riverbeds or volcanic ash deposits. Next, silica-rich groundwater permeates the wood, depositing quartz crystals in its cellular structure. Over time, layers of agate may form within cavities or voids, creating the banded patterns characteristic of agate. This layering can take thousands of years per millimeter, depending on silica concentration and environmental stability. Finally, erosion exposes the petrified wood, revealing its mineralized beauty. Each stage is contingent on specific conditions, making agate formation a testament to nature’s patience and precision.

Practical considerations for enthusiasts or collectors include recognizing that agate petrified wood is not a quick-forming material. While synthetic methods can replicate petrification in decades, natural specimens are the result of millennia of geological processes. When examining a piece, look for signs of its formation history, such as well-defined cell structures or vibrant banding, which indicate prolonged silica deposition. For those interested in witnessing early stages of petrification, regions with active silica-rich water sources, like hot springs or volcanic areas, offer opportunities to observe ongoing mineralization. However, collecting natural specimens requires adherence to local regulations, as many petrified wood sites are protected.

In conclusion, the formation of agate petrified wood is a slow, intricate process shaped by silica availability, temperature, and pressure. Its timeline, ranging from thousands to millions of years, underscores the rarity and value of these geological treasures. By understanding the steps and conditions involved, one gains a deeper appreciation for the natural artistry embedded in each piece. Whether for scientific study or aesthetic enjoyment, agate petrified wood serves as a tangible link to Earth’s ancient past, reminding us of the enduring beauty born from time and transformation.

Understanding the Lifespan of Chemicals in Pressure-Treated Wood

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Petrified Wood Transformation Timeline

The transformation of wood into petrified wood, particularly agatized petrified wood, is a geological marvel that spans millions of years. It begins with the burial of organic material under sediment, where oxygen is limited, preventing complete decay. Groundwater rich in dissolved minerals like silica then seeps into the wood, replacing its cellular structure with minerals in a process called permineralization. This initial stage can take anywhere from 1,000 to 10,000 years, depending on the mineral content of the surrounding environment and the rate of groundwater flow.

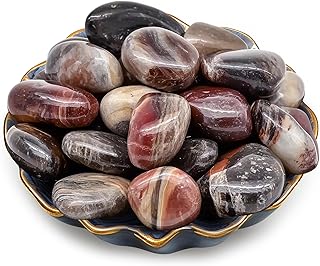

Once permineralization begins, the true artistry of nature unfolds. Agate petrified wood, prized for its vibrant colors and intricate patterns, forms when silica-rich solutions crystallize as chalcedony or quartz within the wood’s pores and cavities. This stage is highly dependent on the chemical composition of the groundwater and the presence of trace elements like iron, manganese, and carbon. For example, iron oxides can create reds and yellows, while manganese oxides produce blacks and browns. The crystallization process can take millions of years, with the most striking agatized specimens often requiring 5 to 20 million years to develop their full beauty.

Comparatively, not all petrified wood becomes agatized. Standard petrified wood, which lacks the colorful banding of agate, forms more rapidly and under less specific conditions. The key difference lies in the uniformity of mineral deposition and the presence of impurities that create the agate’s characteristic patterns. Agatized wood is thus a rarer and more time-intensive product of the petrification process, making it highly sought after by collectors and enthusiasts.

Practical tips for identifying agatized petrified wood include examining its surface for translucent, banded patterns and testing its hardness (typically 7 on the Mohs scale, similar to quartz). While the transformation timeline is beyond human control, understanding the process can deepen appreciation for these ancient treasures. For those interested in collecting, reputable sources and ethical practices are essential, as many prime locations for petrified wood are protected by law.

In conclusion, the journey from wood to agatized petrified wood is a testament to the patience of geological processes. Spanning millennia, it involves permineralization, crystallization, and the slow infusion of minerals that create its distinctive beauty. Whether admired for its scientific significance or aesthetic appeal, agatized petrified wood offers a tangible connection to Earth’s distant past, reminding us of the vast timescales that shape our world.

Curing Murtle Wood: Understanding the Timeframe for Optimal Results

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$33.99 $35.7

Role of Silica in Agatization

Silica, in the form of dissolved silicon dioxide (SiO₂), is the linchpin of agatization—the process that transforms organic wood into agate-filled petrified wood. When groundwater rich in silica percolates through buried wood, it initiates a mineral replacement process. Cell by cell, the organic material is replicated by silica deposits, preserving the wood’s original structure while transforming it into a stone-like material. Without silica, this intricate preservation would be impossible, as it provides the building blocks for the agate’s crystalline lattice.

The concentration of silica in the groundwater directly influences the pace and quality of agatization. Studies suggest that silica-rich solutions with concentrations exceeding 100 ppm (parts per million) accelerate the process, though higher levels (up to 500 ppm) can lead to more uniform and vibrant agate formations. However, silica alone is insufficient; the presence of trace minerals like iron, manganese, and calcium determines the agate’s coloration. For instance, iron oxides produce reds and yellows, while manganese contributes to pinks and blacks.

Temperature and pressure also play critical roles in silica’s transformation. Optimal conditions for agatization occur between 25°C and 50°C, where silica precipitates efficiently without crystallizing into quartz. Below 25°C, the process slows dramatically, while above 50°C, the silica may form coarse quartz crystals instead of the fine-grained agate. This delicate balance underscores why agatization is most successful in sedimentary environments like riverbeds and floodplains, where temperature fluctuations are minimal.

Practical applications of this knowledge can guide fossil enthusiasts and geologists in identifying potential agatization sites. Look for areas with historical volcanic activity, as volcanic ash is a primary source of silica. Additionally, test groundwater silica levels using portable meters; readings above 150 ppm indicate favorable conditions. For those attempting artificial agatization, maintain a controlled environment with temperatures around 35°C and silica concentrations of 300–400 ppm for optimal results.

In summary, silica is not merely a component of agatization but its driving force. Its availability, concentration, and interaction with environmental factors dictate the duration and outcome of the process. Understanding these dynamics allows for both the appreciation of natural agate petrified wood and the replication of this ancient process in laboratory settings. Without silica’s unique properties, the world would be devoid of these mesmerizing geological wonders.

Understanding Cottonwood Tree Shedding: Duration and Seasonal Patterns

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$6.99

Environmental Factors Affecting Speed

The formation of agate petrified wood is a geological process influenced by various environmental factors that dictate its speed and quality. One critical factor is the mineral composition of the surrounding sediment. Silica-rich environments, such as ancient riverbeds or volcanic ash deposits, accelerate the process by providing abundant silica needed for petrification. For instance, wood buried in ash from a silica-rich volcanic eruption can begin mineralization within decades, while wood in silica-poor sediments may take millennia to show significant transformation.

Temperature and pressure also play pivotal roles in determining the speed of petrification. Higher temperatures, typically found in deep sedimentary basins, increase the rate of chemical reactions, reducing the time required for silica to infiltrate the wood’s cellular structure. However, extreme temperatures can degrade organic material before petrification begins, so an optimal range (50–100°C) is necessary. Pressure, often from overlying sediment, compacts the wood and forces minerals into its pores, but excessive pressure can crush the wood, destroying its fibrous structure.

Water availability and pH levels are equally important. Groundwater rich in dissolved minerals acts as a transport medium for silica, facilitating its movement into the wood. A neutral to slightly acidic pH (6.0–7.5) enhances silica solubility, speeding up the process. In arid environments with limited groundwater, petrification may stall or occur at a glacial pace. Conversely, waterlogged conditions can promote decay before mineralization begins, underscoring the need for a balanced moisture environment.

Finally, biological activity in the surrounding soil can either hinder or support petrification. Microorganisms that decompose wood can outpace mineralization in nutrient-rich soils, leaving little organic material to petrify. In contrast, sterile or low-nutrient environments minimize decay, preserving the wood’s structure for longer periods. For enthusiasts seeking to replicate this process, burying wood in silica-rich sand or clay, maintaining a pH of 6.5, and ensuring consistent moisture can expedite petrification, though results still require years, not months.

Understanding these environmental factors allows both scientists and hobbyists to predict and manipulate the conditions necessary for agate petrified wood formation. While nature’s timeline is often measured in centuries, human intervention can shorten this process, albeit with varying degrees of success. The key lies in replicating the precise conditions that nature has perfected over millennia.

Treated Wood Fence Lifespan: Factors Affecting Durability and Longevity

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Comparison with Other Fossilization Methods

Petrified wood, particularly agatized varieties, stands out among fossilization processes due to its mineral replacement mechanism, which contrasts sharply with other methods like compression, carbonization, or mold-and-cast preservation. While compression fossils, such as those found in coal deposits, form over thousands to millions of years under intense pressure, agate petrified wood requires a unique interplay of silica-rich groundwater and void-filling processes, typically spanning 100,000 to several million years. This method not only preserves the wood’s cellular structure but also transforms it into a gemstone-like material, a feature absent in compression fossils, which often retain only the plant’s carbon residue.

Carbonization, another common fossilization method, involves the distillation of organic material into thin carbon films, as seen in fossilized leaves or ferns. This process is significantly faster, often occurring within 10,000 years, and relies on anaerobic conditions to prevent decay. However, unlike agatized wood, carbonized fossils lack three-dimensional preservation and are fragile, making them less durable for geological study or display. Agate petrified wood, by contrast, is a robust, mineralized replica of the original wood, showcasing intricate details like growth rings and cellular structures, a testament to its slower, more meticulous formation process.

Mold-and-cast fossils, such as those of ammonites or trilobites, form when sediments fill the void left by a decaying organism, later hardening into a replica. This method can take anywhere from 10,000 to 1 million years, depending on sedimentation rates and environmental conditions. While mold-and-cast fossils excel at preserving external shapes, they rarely capture internal structures. Agate petrified wood, however, achieves both external and internal preservation through the gradual infiltration of silica, creating a fossil that is both structurally and aesthetically superior, though at the cost of a much longer formation timeline.

Practically, understanding these differences is crucial for paleontologists and collectors. For instance, if one seeks rapid fossilization evidence, carbonization or mold-and-cast processes might yield results within a few millennia. However, for those interested in durable, detailed specimens, agate petrified wood is unparalleled, despite its formation requiring geological patience. To accelerate the study of such fossils, researchers often compare specimens from different fossilization methods, using agatized wood as a benchmark for cellular preservation and compression fossils for broader ecological context. This comparative approach enriches our understanding of ancient ecosystems and the processes that shape them.

Acacia Wood Durability: Outdoor Lifespan and Maintenance Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of forming agate petrified wood typically takes millions of years, often ranging from 5 to 50 million years, depending on environmental conditions and mineral availability.

Factors such as the type of wood, the mineral content of the surrounding sediment, temperature, pressure, and the rate of groundwater flow all influence the duration of petrification.

While rare, accelerated petrification can occur in environments with high silica concentrations and optimal conditions, potentially reducing the process to tens of thousands of years, but it still requires a very long time compared to human timescales.