Woodpeckers are fascinating birds known for their distinctive drumming sounds and ability to peck into trees with remarkable precision. One of the most intriguing aspects of these birds is their tongue, which plays a crucial role in their feeding habits. A woodpecker’s tongue is exceptionally long, often extending far beyond the tip of its bill, and is uniquely adapted to extract insects from deep within tree bark. The length of a woodpecker’s tongue varies by species, with some, like the Red-bellied Woodpecker, having tongues that can reach up to 4 inches long, while others, such as the Northern Flicker, boast tongues that can extend up to an astonishing 5 inches. This extraordinary length, combined with its sticky, barbed tip, allows woodpeckers to efficiently capture prey and navigate the intricate tunnels they create in trees. Understanding the length and function of a woodpecker’s tongue provides valuable insights into their specialized anatomy and survival strategies in the wild.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Tongue Length by Species: Different woodpecker species have varying tongue lengths, adapted to their feeding habits

- Tongue Structure: Woodpeckers' tongues are long, barbed, and sticky, aiding in insect extraction

- Tongue Wrapping: Their tongues wrap around the skull when retracted, accommodating extra length

- Feeding Adaptation: Long tongues help reach deep into tree bark for larvae and insects

- Measurement Examples: Some woodpeckers have tongues up to 4 inches long, relative to body size

Tongue Length by Species: Different woodpecker species have varying tongue lengths, adapted to their feeding habits

Woodpeckers, with their remarkable adaptations, showcase a fascinating diversity in tongue length, a feature intricately tied to their feeding habits. For instance, the Red-bellied Woodpecker, a common sight in North American backyards, has a tongue that can extend up to 2 inches beyond its bill tip. This moderate length is perfectly suited for extracting insects from bark crevices, a primary component of its diet. In contrast, the Acorn Woodpecker, known for its acorn storage behavior, has a slightly shorter tongue, reflecting its reliance on both insects and plant matter. These variations highlight how tongue length is not a one-size-fits-all trait but a specialized tool shaped by evolutionary pressures.

Consider the extreme case of the Black-backed Woodpecker, a species that thrives in burned forests. Its tongue can extend up to 4 inches, allowing it to probe deep into charred wood to extract wood-boring beetle larvae. This adaptation is crucial for survival in its niche habitat, where food sources are often hidden beneath layers of damaged bark. On the other end of the spectrum, the tiny Downy Woodpecker, the smallest in North America, has a tongue proportionate to its size, typically around 1 inch, which is sufficient for its diet of ants and other small insects. These examples illustrate how tongue length is a precise adaptation, tailored to the specific dietary needs of each species.

For those interested in observing these adaptations firsthand, a practical tip is to note the foraging behavior of woodpeckers in different environments. In deciduous forests, look for species like the Hairy Woodpecker, whose longer tongue aids in extracting insects from deeper bark layers. In contrast, woodpeckers in open woodlands, such as the Northern Flicker, often have shorter tongues, as they feed extensively on ants and beetles from the ground. By understanding these correlations, birdwatchers can better predict which species to spot based on habitat and feeding habits.

From a comparative perspective, the tongue length of woodpeckers also reflects their evolutionary history and ecological roles. Species with longer tongues, like the Gila Woodpecker of the southwestern U.S., often have more specialized diets, while those with shorter tongues, such as the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, exhibit broader feeding strategies, including sap-sucking. This diversity underscores the importance of tongue length as a key factor in species differentiation and ecological success. Whether you're a researcher, birder, or simply curious, understanding these adaptations offers a deeper appreciation for the intricate ways woodpeckers interact with their environments.

Drying Wood Boards: Essential Tips for Optimal Moisture Removal

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$3.99

Tongue Structure: Woodpeckers' tongues are long, barbed, and sticky, aiding in insect extraction

Woodpeckers' tongues are marvels of evolutionary engineering, specifically designed to extract insects from deep within tree bark. These tongues are remarkably long, often wrapping around the skull and extending beyond the tip of the bill, reaching lengths of up to 4 inches in some species like the Northern Flicker. This extraordinary length allows woodpeckers to probe crevices that would otherwise be inaccessible, giving them a competitive edge in foraging.

The structure of a woodpecker’s tongue is as fascinating as its length. It is barbed at the tip, resembling a spear, which helps impale or grasp prey. Additionally, the tongue is coated in a sticky saliva, akin to natural glue, ensuring that insects cannot escape once caught. This combination of barbs and adhesive properties makes the tongue a highly effective tool for insect extraction, particularly for larvae buried deep within wood.

To understand the tongue’s functionality, consider its movement. When not in use, the tongue is stored in a specialized sheath that wraps around the skull, anchored by a bone called the hyoid. This unique adaptation prevents the tongue from drying out and allows it to retract efficiently. When hunting, the tongue is shot forward with incredible speed, aided by elastic tissues that act like a spring. This mechanism ensures precision and efficiency in capturing prey.

For those interested in observing woodpeckers in action, look for signs of their foraging, such as holes in trees or accumulations of wood chips at the base of trunks. Binoculars can help you spot the rapid movements of their bills and the occasional flash of their tongues as they extract insects. Understanding the tongue’s structure not only deepens appreciation for these birds but also highlights the intricate ways nature adapts to specific ecological niches.

In practical terms, this knowledge can inform conservation efforts. Protecting old-growth forests, where woodpeckers find ample insect prey, is crucial. Additionally, creating artificial nesting sites can support woodpecker populations in areas where natural cavities are scarce. By preserving their habitats and understanding their unique adaptations, we can ensure these remarkable birds continue to thrive.

The Surprising History and Evolution of Pressed Wood Over Time

You may want to see also

Explore related products

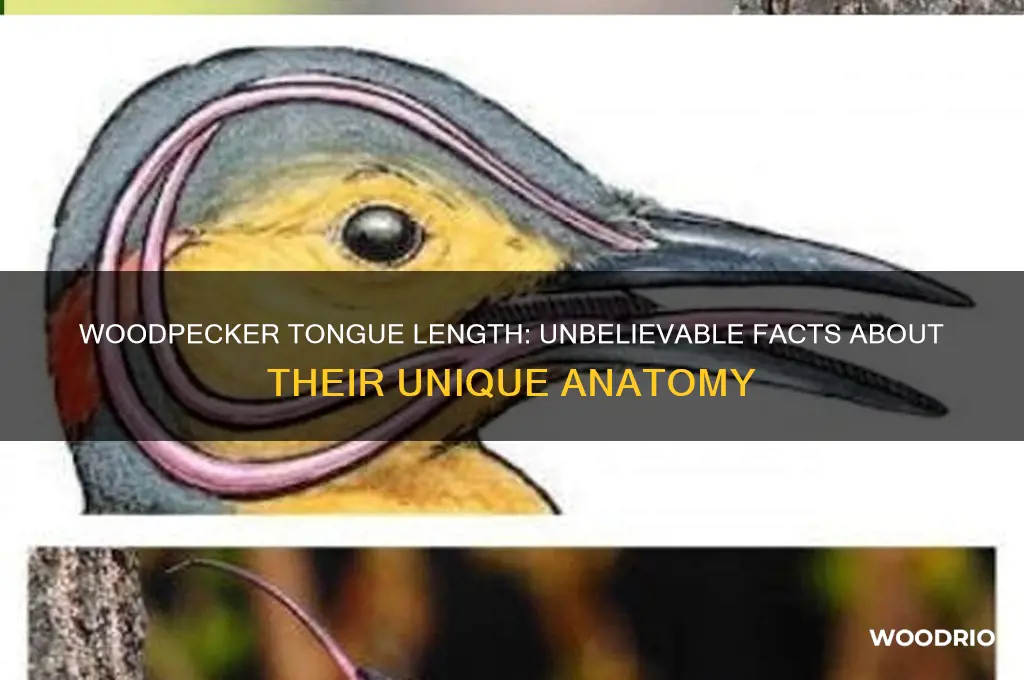

Tongue Wrapping: Their tongues wrap around the skull when retracted, accommodating extra length

Woodpeckers possess one of the most extraordinary anatomical adaptations in the animal kingdom: their tongues can extend far beyond their beaks, reaching deep into tree bark to extract insects. But what’s truly remarkable is how they store this elongated organ when not in use. Unlike most birds, a woodpecker’s tongue doesn’t simply retract into the mouth. Instead, it wraps around the back of the skull, forming a loop that accommodates its extraordinary length. This unique mechanism allows the tongue to be up to three times the length of the bird’s bill without causing obstruction or discomfort.

To understand the practicality of this adaptation, consider the physics involved. A woodpecker’s tongue can extend up to 4 inches in smaller species and over 6 inches in larger ones, such as the pileated woodpecker. If left uncoiled within the head, such length would be impossible to manage. By wrapping around the skull, the tongue not only fits neatly but also remains protected and ready for rapid deployment. This system is akin to a high-precision retracting tape measure, optimized for both storage and function.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this tongue-wrapping mechanism is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. It solves a critical problem for woodpeckers, whose survival depends on accessing hidden prey. The tongue’s hyoid bone, a flexible structure extending from the beak to the skull, acts as a guide for the wrapping process. This bone is so elongated that it exits the base of the beak, loops under the skin, and re-enters the skull, creating a pathway for the tongue. Without this adaptation, woodpeckers would lack the foraging efficiency that sustains them.

For those curious about observing this phenomenon, dissecting a woodpecker specimen (ethically sourced for educational purposes) reveals the tongue’s intricate path. Alternatively, high-speed footage of a woodpecker feeding shows the tongue’s lightning-fast extension and retraction. Practical tips for birdwatchers include looking for species like the red-bellied woodpecker or the downy woodpecker, whose feeding behaviors highlight this adaptation. Understanding this mechanism not only deepens appreciation for woodpeckers but also underscores the marvels of evolutionary biology.

In essence, the tongue-wrapping ability of woodpeckers is a masterclass in biological problem-solving. It transforms a potential anatomical challenge into a functional advantage, ensuring these birds thrive in their ecological niche. Whether you’re a biologist, a bird enthusiast, or simply someone fascinated by nature’s quirks, this adaptation offers a compelling example of how form follows function in the natural world.

Linseed Oil Curing Time: How Long to Fully Cure Wood?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Feeding Adaptation: Long tongues help reach deep into tree bark for larvae and insects

Woodpeckers possess remarkably long, barbed tongues that can extend far beyond the length of their bills, a feature that is not just a biological curiosity but a critical feeding adaptation. These tongues, often reaching up to 4 inches in length, are specifically designed to extract larvae and insects from deep within tree bark. The sticky, barbed tip of the tongue acts like a natural grappling hook, ensnaring prey that would otherwise be inaccessible. This anatomical marvel allows woodpeckers to exploit a niche that few other birds can, making them highly efficient foragers in their woodland habitats.

Consider the process: a woodpecker drills a hole into a tree with its chisel-like beak, creating an opening just wide enough to insert its tongue. The tongue, coated in a sticky saliva, is then darted into the cavity, adhering to any insects or larvae hiding within. This method is not only precise but also energy-efficient, as it minimizes the need for excessive pecking or probing. For example, the Red-bellied Woodpecker’s tongue can extend up to 2 inches past the tip of its bill, enabling it to reach prey in deeper crevices than its beak alone could access.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this adaptation highlights the principle of form following function. The elongated hyoid bone, which supports the tongue, wraps around the woodpecker’s skull, allowing the tongue to retract and extend with remarkable agility. This anatomical arrangement is a testament to the pressures of natural selection, where only the most efficient foragers thrive. Without such a tongue, woodpeckers would struggle to sustain their high-energy lifestyles, which require a constant intake of protein-rich insects.

Practical observation of this adaptation can be a rewarding experience for birdwatchers. To witness it in action, look for woodpeckers probing trees with rhythmic taps, then watch as they pause to extract prey. Binoculars or a spotting scope can enhance the view, revealing the lightning-fast movement of the tongue. For those interested in attracting woodpeckers to their yards, providing suet feeders or leaving dead trees (snags) as natural insect habitats can encourage these birds to showcase their feeding prowess.

In conclusion, the woodpecker’s long tongue is not merely a tool but a finely tuned instrument of survival. Its length, stickiness, and agility enable woodpeckers to access food sources that are out of reach for most other birds. This adaptation underscores the intricate relationship between form and function in nature, offering both scientific insight and practical appreciation for one of the forest’s most fascinating inhabitants.

Mastering Wood Bending: Optimal Steaming Times for Perfect Curves

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Measurement Examples: Some woodpeckers have tongues up to 4 inches long, relative to body size

Woodpeckers' tongues are marvels of evolutionary adaptation, with some species boasting lengths up to 4 inches—a staggering proportion relative to their body size. For context, imagine a human tongue extending nearly a foot long. This extraordinary length serves a critical purpose: extracting insects from deep within tree bark. The tongue wraps around the skull, anchored by a specialized bone called the hyoid, which acts as a natural slingshot, allowing it to dart out with precision and speed.

Consider the pileated woodpecker, a striking example of this phenomenon. Its tongue, measuring up to 4 inches, is nearly as long as its bill. This adaptation enables it to probe deep crevices in decaying wood, where carpenter ants and beetle larvae hide. For birdwatchers, observing this behavior offers a tangible measurement example: if the woodpecker’s body is roughly 19 inches long, its tongue represents a fifth of its total length—a ratio that underscores nature’s ingenuity.

To visualize this, try a simple exercise: place a ruler beside a pencil to simulate the woodpecker’s body and tongue. Mark 4 inches on the ruler, then compare it to the pencil’s length. This hands-on approach highlights the tongue’s disproportionate size and its functional significance. For educators, this activity can engage students in discussions about biological adaptations, using the woodpecker as a case study in proportional measurement.

While 4 inches may seem modest, it’s a game-changer for survival. The tongue’s length, combined with its sticky saliva, ensures woodpeckers can secure prey efficiently, even in hard-to-reach spots. This measurement isn’t arbitrary—it’s the result of millions of years of evolution, fine-tuned to meet the demands of their ecological niche. Next time you spot a woodpecker, remember: that tongue isn’t just long; it’s a testament to nature’s precision engineering.

Drying Wood Post-Leak: Understanding the Timeframe for Effective Restoration

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A woodpecker's tongue can extend up to 4 inches (10 cm) beyond its beak, depending on the species.

Woodpeckers have long, sticky tongues to extract insects from deep within tree bark, aiding their feeding habits.

Yes, a woodpecker's tongue is often longer than its beak, allowing it to reach prey hidden in narrow crevices.

No, tongue length varies by species, with some having shorter tongues compared to others, depending on their diet and habitat.

![[2 pack] KN FLAX Tongue Scraper [Medical Grade] Reduce Bad Breath Maintains Oral Care 100% BPA Free Metal Tongue Scraper, Tongue Cleaner for Adults and Kids, Easy to Use with Non-Synthetic Handle](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71uvyz8JY4L._AC_UL320_.jpg)