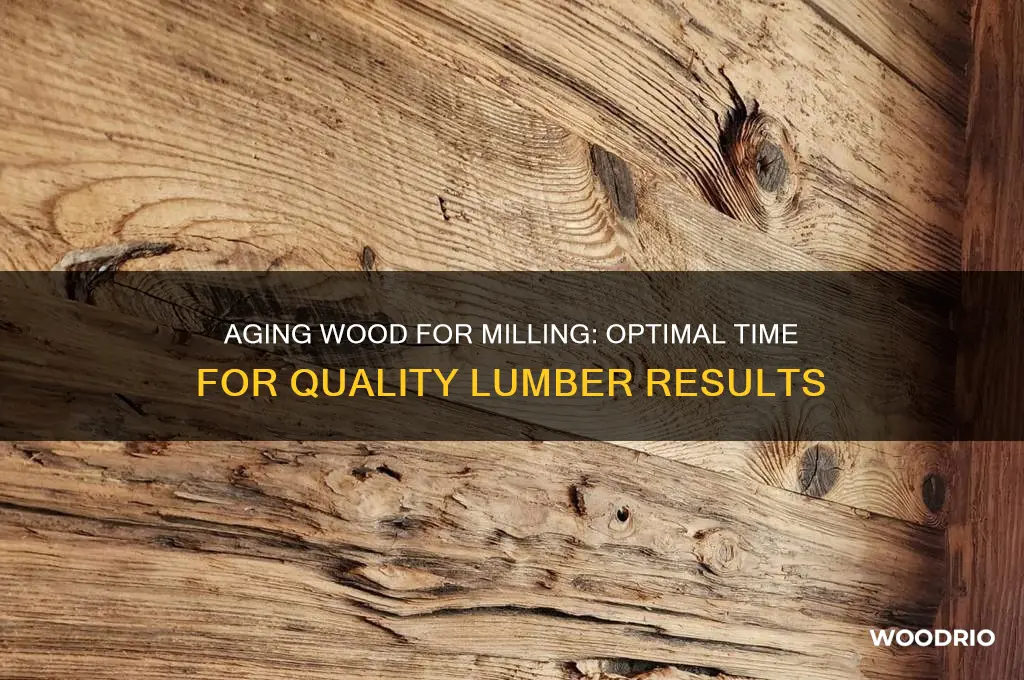

The process of aging wood before milling is a crucial step in woodworking, as it significantly impacts the quality, stability, and durability of the final product. Wood needs to age or dry properly to reduce its moisture content, which can otherwise lead to warping, cracking, or shrinking after milling. The time required for wood to age varies depending on factors such as the wood species, initial moisture content, and environmental conditions. Hardwoods, for example, typically require a longer aging period compared to softwoods, often ranging from several months to a few years. Proper aging ensures that the wood reaches an equilibrium moisture content (EMC) that matches the humidity levels of its intended environment, minimizing the risk of structural issues in the finished piece.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Minimum Aging Time for Softwoods | 6 months to 1 year (varies by species and moisture content) |

| Minimum Aging Time for Hardwoods | 1 to 2 years (varies by species and moisture content) |

| Optimal Aging Time for Stability | 2 to 5 years (reduces warping, cracking, and moisture-related issues) |

| Moisture Content Goal | 8-12% (kiln-dried or air-dried to match local humidity conditions) |

| Factors Affecting Aging Time | Wood species, initial moisture content, climate, and storage method |

| Purpose of Aging | Reduces moisture content, improves dimensional stability, enhances workability |

| Alternative Methods | Kiln drying (accelerates process but requires expertise) |

| Storage Conditions | Stacked with stickers, covered, and in a well-ventilated area |

| Commonly Aged Woods | Oak, maple, walnut, pine, cedar (times vary by species) |

| Signs of Readiness | Stable moisture content, minimal cracking, and consistent color |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Ideal Aging Time for Different Wood Species

The aging process of wood is a critical factor in determining its quality and workability, with different species requiring varying durations to reach optimal conditions for milling. For instance, hardwoods like oak and maple typically need at least 6 to 12 months of air drying to reduce moisture content to around 12-15%, a level suitable for most woodworking projects. This initial phase is crucial for minimizing warping and cracking during the milling process. Softwoods, such as pine and cedar, often dry faster due to their lower density, usually achieving milling readiness within 3 to 6 months under similar conditions. However, these are general guidelines, and the ideal aging time can vary significantly based on the specific wood species, environmental conditions, and intended use.

Consider the example of black walnut, a prized hardwood known for its rich color and durability. To maximize its stability and aesthetic appeal, black walnut should be aged for a minimum of 1 to 2 years. This extended period allows the wood to naturally shed excess moisture and for the tannins to oxidize, enhancing its natural color. In contrast, cherry wood, another popular hardwood, benefits from a slightly shorter aging period of 9 to 18 months. This duration ensures that the wood retains its vibrant red hues while achieving the necessary moisture levels for milling. Proper stacking and ventilation during the aging process are essential for both species to prevent mold and ensure even drying.

For those working with exotic woods like teak or mahogany, patience is paramount. Teak, renowned for its resistance to decay and insects, requires 2 to 3 years of aging to fully stabilize and develop its characteristic oily surface. Mahogany, prized for its beauty and workability, should be aged for at least 1.5 to 2.5 years to achieve optimal moisture content and to allow its natural resins to mature. These longer aging times are investments in the wood’s long-term performance and appearance, particularly in outdoor or high-moisture applications.

Instructively, the aging process can be accelerated with kiln drying, but this method requires careful monitoring to avoid over-drying or case hardening. Kiln-dried wood can be ready for milling in as little as 2 to 4 weeks for softwoods and 4 to 8 weeks for hardwoods, depending on the species and kiln settings. However, kiln drying is not a substitute for natural aging in all cases, as some woods, like oak, benefit from the slower, natural process that allows internal stresses to dissipate. Always refer to species-specific guidelines and conduct moisture tests to ensure the wood is adequately dried before milling.

Persuasively, understanding and respecting the ideal aging time for different wood species is not just a matter of craftsmanship but also of sustainability. Properly aged wood is less likely to warp, crack, or fail over time, reducing waste and the need for replacements. For example, using prematurely milled wood in construction or furniture making can lead to costly repairs and dissatisfied clients. By investing time in the aging process, woodworkers and manufacturers can produce higher-quality products that stand the test of time, ultimately benefiting both the environment and their reputation.

Durability of Faux Wood Shutters: Lifespan and Maintenance Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Effects of Moisture Content on Aging Wood

Wood's moisture content is a critical factor in its aging process, directly influencing its stability, strength, and workability before milling. Freshly cut wood, or "green" wood, typically contains 30% to 200% moisture by weight, depending on the species. Milling such wood can lead to warping, cracking, and dimensional changes as it dries. To mitigate these issues, wood must be air-dried or kiln-dried to reduce moisture content to 8% to 12%, the ideal range for most woodworking applications. This process can take anywhere from several months to a year, depending on the species, thickness, and environmental conditions. For example, oak may require 6 to 12 months of air-drying, while softer woods like pine may dry in 3 to 6 months.

The relationship between moisture content and aging is not linear; it involves a delicate balance. Wood cells absorb and release moisture in response to humidity changes, causing expansion and contraction. If wood dries too quickly, internal stresses build up, leading to checks (surface cracks) or honeycombing (internal voids). Conversely, slow drying allows wood fibers to adjust gradually, minimizing defects. Kiln-drying accelerates this process using controlled heat and humidity but requires precise monitoring to avoid over-drying. For instance, a kiln schedule for hardwoods might start at 100°F and gradually increase to 140°F over 2 to 3 weeks, maintaining relative humidity at 70% initially and reducing it to 30% by the end.

Practical tips for managing moisture content during aging include stacking wood with stickers (spacers) to promote airflow, covering piles to protect from rain while allowing ventilation, and using a moisture meter to monitor progress. For air-drying, aim for a stack height of 6 to 8 feet and ensure the wood is stored in a well-ventilated area with consistent humidity. Kiln operators should follow species-specific schedules, as denser woods like walnut require lower temperatures and longer drying times compared to less dense species like fir. Ignoring these details can result in wood that is either too wet for milling or too dry to work with effectively.

Comparing air-drying and kiln-drying highlights their trade-offs. Air-drying is cost-effective and environmentally friendly but time-consuming and dependent on weather conditions. Kiln-drying is faster and more controllable but requires significant energy input and specialized equipment. For hobbyists or small-scale operations, air-drying is often the practical choice, while commercial mills favor kiln-drying for efficiency. Regardless of method, the goal remains the same: achieving a moisture content that aligns with the wood’s final use, whether for furniture, flooring, or structural elements.

In conclusion, moisture content is not just a byproduct of aging wood—it is a central variable that determines the success of the milling process. Proper management of this factor ensures wood reaches its optimal state for working, combining durability with aesthetic appeal. By understanding the science behind moisture movement and applying practical techniques, woodworkers can transform raw timber into a material that stands the test of time.

Chicken of the Woods Growth Timeline: How Long to Harvest?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasoning Methods for Faster Wood Aging

Wood typically requires 6 months to 2 years to air-dry sufficiently for milling, depending on thickness and species. However, this timeline can be accelerated with strategic seasoning methods. Kiln drying, for instance, reduces this period to days or weeks by controlling temperature and humidity in a specialized chamber. For a 1-inch thick hardwood board, a kiln can achieve optimal moisture levels in 3–7 days at 140°F (60°C), compared to months of air drying. This method is costly but efficient, making it ideal for commercial operations.

For those without access to a kiln, solar drying offers a cost-effective alternative. Construct a solar kiln using clear plastic sheeting, a wooden frame, and vents for airflow. Place the wood inside, ensuring it’s stacked with spacers for air circulation. The greenhouse effect raises internal temperatures, accelerating moisture evaporation. A well-designed solar kiln can reduce drying time by 50%, though results depend on climate and sunlight exposure. Monitor moisture levels with a wood moisture meter, aiming for 6–8% for indoor use.

Chemical treatments can also expedite seasoning, though they’re less common due to environmental concerns. Applying a solution of 5–10% polyethylene glycol (PEG) to green wood penetrates the cells, reducing shrinkage and warping during drying. This method is particularly useful for high-value hardwoods like oak or walnut. However, ensure proper ventilation and protective gear when handling chemicals, and allow treated wood to air-dry for at least 2 weeks before milling.

Steaming is another technique that softens wood fibers, making it easier to bend or cut while reducing drying time. Expose the wood to steam at 212°F (100°C) for 30–60 minutes, depending on thickness. This process raises the wood’s temperature, accelerating moisture release. Steamed wood should then be air-dried or kiln-dried to complete the seasoning process. While effective, steaming requires specialized equipment and is best suited for specific applications like furniture making or boatbuilding.

Lastly, combining methods can yield the fastest results. For example, pre-dry wood in a solar kiln for 2–3 weeks, then finish in a kiln for 3–5 days. This hybrid approach balances cost and efficiency, ensuring wood is ready for milling in a fraction of the traditional time. Always test small batches first to fine-tune the process for your specific wood species and climate conditions. With the right techniques, you can significantly reduce aging time without compromising wood quality.

The Ancient Process: How Long Does Petrified Wood Form?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Signs Wood is Ready for Milling

Wood doesn’t come with an expiration date, but it does signal when it’s ready for milling. One of the most reliable indicators is moisture content, which should ideally fall between 8% and 12% for most woodworking projects. At this range, the wood is stable enough to resist warping, cracking, or shrinking after being cut and shaped. A moisture meter is an essential tool here—simply insert the probes into the wood and wait for the reading. If the moisture content is too high, further drying is necessary; if it’s within range, milling can begin.

Another telltale sign is the wood’s weight. Properly seasoned wood feels noticeably lighter than freshly cut timber due to the evaporation of water. To test this, compare a piece of aged wood with a freshly cut sample of the same species and size. The difference in weight is a practical, hands-on way to gauge readiness without relying solely on tools. However, weight alone isn’t definitive—it should always be paired with moisture content testing for accuracy.

Cracks and checks in the wood’s surface can also indicate readiness, but they require careful interpretation. Fine, hairline checks on the ends of boards are common during drying and often signify that moisture is escaping properly. However, deep, widespread cracks suggest the wood dried too quickly or unevenly, which can compromise its structural integrity. If the checks are minimal and confined to the ends, the wood is likely ready for milling. If they’re severe, it may be unsalvageable.

Finally, the wood’s color and texture can provide subtle clues. As wood ages, it often darkens slightly and develops a more uniform appearance. Freshly cut wood typically has a brighter, wetter look, while seasoned wood appears matte and consistent. Running your hand along the surface can also reveal readiness—smoothness without a sticky or rough feel indicates the natural oils and resins have stabilized. These visual and tactile cues, combined with moisture testing, create a comprehensive assessment of milling readiness.

Installing a Wood Gate: Timeframe and Tips for a Smooth Process

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of Aging on Wood Strength & Stability

Wood aging is a transformative process that significantly influences its strength and stability, making it a critical consideration before milling. As wood dries and ages, its moisture content decreases, leading to a reduction in internal stresses. This natural seasoning process can take anywhere from 6 months to 2 years, depending on the species and environmental conditions. For instance, hardwoods like oak and maple typically require longer aging periods compared to softwoods like pine. Properly aged wood exhibits less warping, cracking, and shrinkage, ensuring a more stable end product. However, aging alone is not a one-size-fits-all solution; it must be paired with controlled drying methods to maximize its benefits.

The impact of aging on wood strength is twofold. On one hand, aging allows for the gradual release of bound moisture, which strengthens the wood’s cellular structure by reducing internal tension. On the other hand, excessive aging can lead to degradation, particularly in outdoor environments where UV exposure and moisture fluctuations accelerate decay. For example, wood aged beyond 5 years in humid climates may begin to lose its structural integrity due to fungal growth or insect damage. To mitigate this, wood intended for milling should be stored in a controlled environment, such as a covered, well-ventilated shed, to balance aging benefits with preservation.

Stability is another critical factor influenced by aging. Freshly cut wood, or "green wood," contains high moisture levels, making it prone to movement as it dries. Aging reduces this moisture content, minimizing dimensional changes once the wood is milled. A practical tip for assessing stability is to measure the wood’s moisture content using a moisture meter; ideal levels for milling range between 8–12% for most applications. Wood aged to this range is less likely to warp or split, ensuring a more reliable material for construction or craftsmanship.

Comparing aged and unaged wood highlights the importance of this process. Unaged wood, when milled prematurely, often results in finished products that twist, bow, or crack over time. In contrast, aged wood provides a more predictable and durable outcome. For instance, furniture made from properly aged walnut retains its shape and structural integrity far longer than that made from freshly cut timber. This underscores the value of patience in woodworking, where the aging period is an investment in the material’s long-term performance.

Instructively, woodworkers and millers can optimize aging by categorizing wood based on its intended use. Structural timber, such as beams or joists, benefits from longer aging periods to ensure maximum strength and stability. Decorative or indoor wood, like paneling or furniture components, may require shorter aging times but still need careful monitoring to avoid over-drying. A useful practice is to document the aging process, noting starting moisture levels, environmental conditions, and periodic measurements. This data-driven approach ensures that the wood is milled at its optimal stage, balancing strength, stability, and usability.

Petrified Oak: Understanding the Timeframe for Wood Fossilization

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wood typically needs to age for 6 to 12 months before milling, depending on the species and moisture content, to ensure it is properly dried and stable.

Yes, the aging time varies by species. Hardwoods like oak or maple may require 1 to 2 years, while softer woods like pine may only need 6 to 12 months.

Aging is necessary because freshly cut wood contains high moisture levels. Milling it immediately can lead to warping, cracking, or shrinkage as it dries.

In dry, warm climates, wood may dry faster (6–9 months), while in humid or cold climates, it may require 12–24 months to reach optimal moisture levels.

Wood is ready for milling when its moisture content is 8–12%, it feels lighter, and it no longer shows signs of cracking or warping during the drying process.